Credits: Michele D’Ottavio, 2010. © MuseoTorino

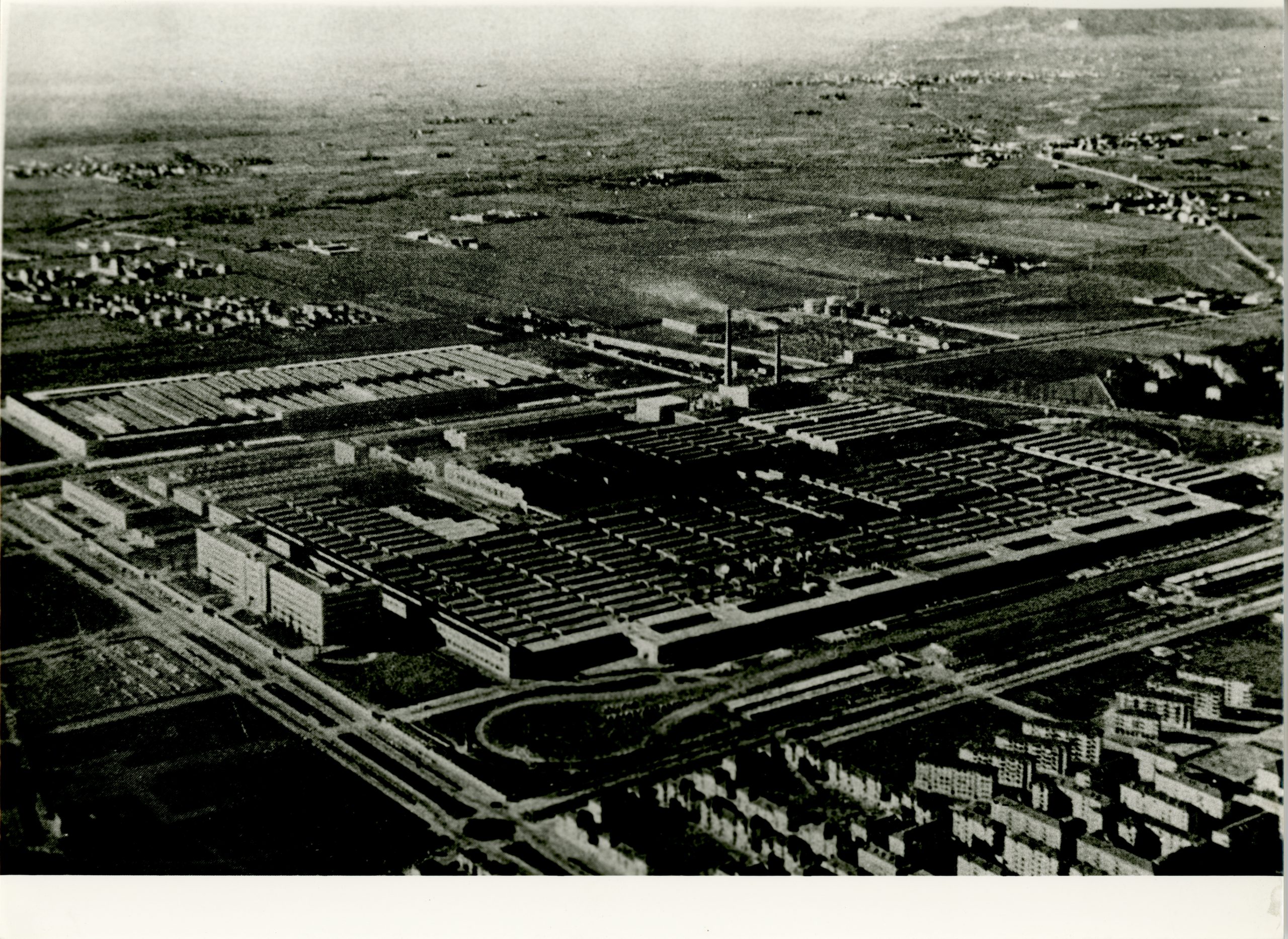

Ah, here we are, I recognise the brand of the famous Fiat 500 factory, Laura!

Ah, here we are, I recognise the brand of the famous Fiat 500 factory, Laura!

Yes, we are here because Fiat was a key site for the opposition to the Fascist regime. As early as March 1943, even before the Allied landing in Sicily and Mussolini’s dismissal, the workers went on strike against the war and Fascism, that was what caused it. From Turin the protest then spread to other industrial cities in northern Italy.

Yes, we are here because Fiat was a key site for the opposition to the Fascist regime. As early as March 1943, even before the Allied landing in Sicily and Mussolini’s dismissal, the workers went on strike against the war and Fascism, that was what caused it. From Turin the protest then spread to other industrial cities in northern Italy.  So those were episodes of Resistance then…

So those were episodes of Resistance then…

Sure, initially based on economic demands. Then, with the Italian Social Republic and the German occupation, the protest became more and more political. A year later, in March 1944, a general strike was called throughout central and northern Italy. In the factories of Turin, like here at Mirafiori, there was a significant level of participation, about 70,000 workers.

Sure, initially based on economic demands. Then, with the Italian Social Republic and the German occupation, the protest became more and more political. A year later, in March 1944, a general strike was called throughout central and northern Italy. In the factories of Turin, like here at Mirafiori, there was a significant level of participation, about 70,000 workers.

A strike in the middle of the war… did it have any consequences?

A strike in the middle of the war… did it have any consequences?

Yes, and they were very harsh: the Nazis and the Fascists reacted immediately with sweeping arrests of the workers, going from house to house. Many of them were deported from Porta Nuova station to concentration camps. About 400 people left Turin, more than 150 of whom worked at Fiat. This is just one example of what happened in all the regions of central and northern Italy!

Yes, and they were very harsh: the Nazis and the Fascists reacted immediately with sweeping arrests of the workers, going from house to house. Many of them were deported from Porta Nuova station to concentration camps. About 400 people left Turin, more than 150 of whom worked at Fiat. This is just one example of what happened in all the regions of central and northern Italy!

Credits: Fondazione Istituto piemontese A. Gramsci, dall’Archivio fotografico della Federazione torinese del Pci.

Thousands of Italian citizens were deported to territories under German control.

In addition to the Jews, almost 24,000 deportees were classified as belonging to a political category (partisans, anti-fascists, strikers, draft dodgers, dissidents, including about 1,500 women) and sent to concentration camps.

A further 10,000 prisoners were sent to camps set up by the Fascists on Italian territory from 1940, such as Fossoli. With the German occupation in 1943, these facilities became transit camps, run by Nazis and Fascists.

Of the approximately 810,000 Italian soldiers captured by the Germans after the armistice, about 630,000 were deported to prison camps in Poland and Germany: identified as Italian Military internees (IMI), in order not to recognise their status as prisoners of war and to deprive them of Red Cross assistance, many of them were employed as forced labourers as part of the German economy.

Finally, about 200,000 Italians – divided roughly in half between civilians rounded up and workers who had left voluntarily over the years and were detained after July 1943 – were compelled into forced labour in the Reich.

Even the memory of the deportations from Italy was fragmented. At the end of the war, the return of deportees was a long and painful process: reintegration was made more complex by the difficulty of bearing witness.

The image of the brave and victorious partisans prevailed in the official narrative of the immediate post-war period but, as the decades passed, the public interest in political deportation grew.

In 2000, January 27th, the date of the liberation of Auschwitz, was chosen as a Remembrance Day for the victims of the Holocaust and for political and military deportees. This gave a new relevance to the victims of deportation, initiating many projects, such as the installation of stumbling stones throughout Europe, to remember all the victims of Nazi and Fascist persecution and extermination.

At a public level, however, the memory of racial deportation is more widespread than other memories. On the other hand, a national awareness process to acknowledge the Italian responsibility for the deportations, has been postponed once again.

Finally, the Italian Military internees (IMI), although there were so many of them and they were so significant, have become the subject of systematic studies only since the 1990s.

Finally, the stories of the Internati Militari Italiani, IMI (Italian Military Internee), although so numerous and significant, have been studied only recently.

Places of interest

(Bolzano, Trentino-Alto Adige)

(Milan, Lombardy)

(Trieste, Friuli-Venezia Giulia)

(Carpi, Emilia-Romagna)

(Prato, Tuscany)

(Rome, Lazio)

(Agnone, Molise)

(Tremiti Islands, Apulia)

(Sasso Marconi, Emilia-Romagna)

Watching /reading tips

Diario clandestino

Book

(Giovannino Guareschi, 1949)

L’altra Resistenza: i militari italiani internati in Germania

Book

(Alessandro Natta, 1997)

To know more