Credits: Giulia Zitelli Conti, Isrifar

What a wonderful place, so full of history. But… looking at the ground I noticed that you too have stumbling stones in memory of those deported to the camps. From here on there are so many, why?

What a wonderful place, so full of history. But… looking at the ground I noticed that you too have stumbling stones in memory of those deported to the camps. From here on there are so many, why?

We are in the old Jewish quarter, where the occupants of the ghetto were rounded up on October 16th,1943. Right here, between the Portico of Octavia and the remains of the Theatre of Marcellus, the SS assembled the Jews they had forcibly taken after house to house raids.

We are in the old Jewish quarter, where the occupants of the ghetto were rounded up on October 16th,1943. Right here, between the Portico of Octavia and the remains of the Theatre of Marcellus, the SS assembled the Jews they had forcibly taken after house to house raids.  As they had done in Paris in 1942…

As they had done in Paris in 1942…

Yes, Jan, and here the Nazis were helped out by the census of the Jews following the Racial Laws passed by the Fascist regime.

Yes, Jan, and here the Nazis were helped out by the census of the Jews following the Racial Laws passed by the Fascist regime.

What happened to these people after the round-up?

What happened to these people after the round-up?

1,024, including 200 children, were rounded up and then deported from Tiburtina station to Auschwitz. Once there, 823 were sent immediately to the gas chambers. Only 16 survived and returned home.

1,024, including 200 children, were rounded up and then deported from Tiburtina station to Auschwitz. Once there, 823 were sent immediately to the gas chambers. Only 16 survived and returned home.

Ah, I see that there is a commemorative plaque up there.

Ah, I see that there is a commemorative plaque up there.

Yes, it was put up in the 1960s and it commemorates the Roman and Italian Jews who died in the Nazi camps. A street was also named after that terrible day in 1943.

Yes, it was put up in the 1960s and it commemorates the Roman and Italian Jews who died in the Nazi camps. A street was also named after that terrible day in 1943.

Credits: Federico Patellani © Archivio Federico Patellani – Regione Lombardia / Museo di Fotografia Contemporanea, Milano-Cinisello Balsamo

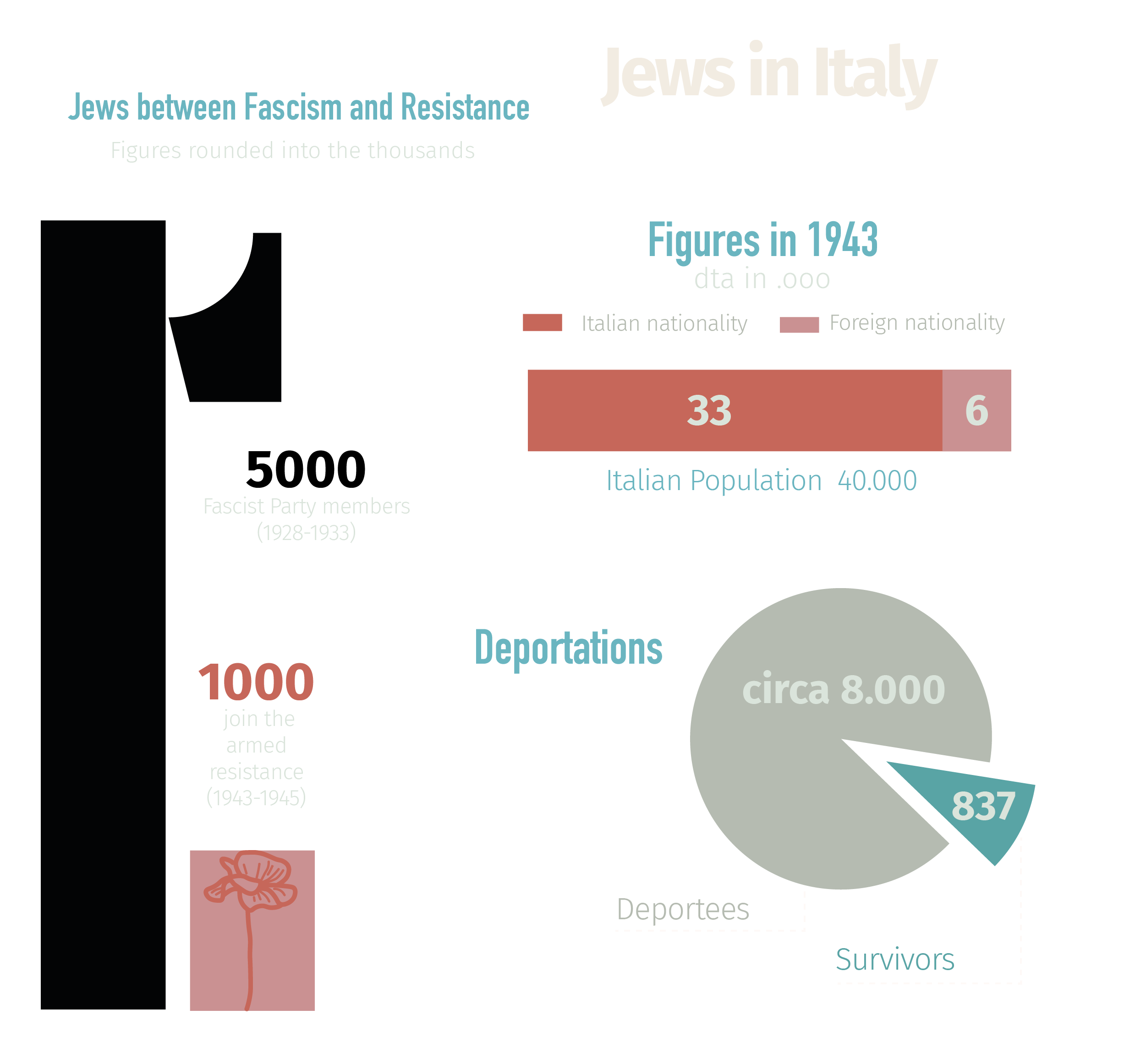

The Fascist regime’s racial propaganda – started in 1936 – was fully implemented in 1938. In that year, the so-called “Manifesto of Racist Scientists” was published; the General Directorate for Demography and Race was created; and a census of Jews living in Italy was taken.

In the autumn the so-called Racial Laws were approved, a set of measures sanctioning the exclusion of Jews from national life: expulsion from schools, public and private institutions, a ban on mixed marriages and much more.

The persecution – which began to the general indifference of the population and without open opposition, not even from the Church – took a dramatic turn in 1943: the Italian Social Republic sanctioned the systematic arrest of Jews and the confiscation of their property, setting up transit and concentration camps on Italian soil. The Nazis, assisted by the Fascists, organised round-ups and deportations.

More than 8,000 Jews were deported from Italy and Italian-occupied areas in France and the Dodecanese to Auschwitz and other concentration and extermination camps, where most of them died.

The awareness of the persecution and extermination of the Jews was not immediate and in Italy – as in Europe – it went through different phases.

In the initial post-war period, the extermination of the Jews was not separated from the general violence of the war, and the story of the partisans took precedence. It was only in the late 1950s that works such as Primo Levi’s If This is a Man and the trial of Adolf Eichmann (Jerusalem 1961) shed light on the Shoah and highlighted the role of witnesses. However, Italian responsibility was lessened and justified by the war; the memory of the racial laws was swept under the carpet until recent years.

Since the 1990s, the Shoah has become a fully-fledged part of the European and Italian political and memorial agenda, especially after the Holocaust Memorial Day was established, and the role of the victims and the ‘righteous’ has come to the fore.

However, revisionism and indifference persist, and there are new waves of anti-Semitism, racism and xenophobia. Moreover, the memory of other racial persecutions, such as those of the Roma and Sinti, is still lacking in public debate.

Places of interest

(Borgo San Dalmazzo, Piedmont)

(Milan, Lombardy)

(Trieste, Friuli-Venezia Giulia)

(Nonantola, Emilia-Romagna)

(Servigliano, Marche)

(Assisi, Umbria)

(Ferramonti di Tarsia, Calabria)

(Venice, Veneto)

(Ferrara, Emilia-Romagna)

Watching /reading tips

L’oro di Roma

Movie

(Carlo Lizzani, 1961)

Se questo è un uomo

Book

(Primo Levi, 1947)

La vita è bella

Movie

(Roberto Benigni, 1997)

Il giardino dei Finzi Contini

Book

(Giorgio Bassani, 1962)

To know more