Credits: Nino Saltalamacchia, Centro Studi Eoliano

Here we are Jan! Our journey begins here!

Here we are Jan! Our journey begins here!

On this island? This is a wonderful place Laura, in the middle of nowhere…

On this island? This is a wonderful place Laura, in the middle of nowhere…

We are on Lipari, in Sicily. In 1927 this island became the main confinement colony for the opponents of the regime. This was the fate of most of the anti-fascist intellectuals or politicians who were sent to remote areas to distance them physically and psychologically from the rest of the country.

We are on Lipari, in Sicily. In 1927 this island became the main confinement colony for the opponents of the regime. This was the fate of most of the anti-fascist intellectuals or politicians who were sent to remote areas to distance them physically and psychologically from the rest of the country. Did they live like in prisons?

Did they live like in prisons?

No, but still it wasn’t easy. They had to return home at specific times, could not go to any kind of meeting places and lived in very difficult conditions.

No, but still it wasn’t easy. They had to return home at specific times, could not go to any kind of meeting places and lived in very difficult conditions.

Did anybody ever manage to escape?

Did anybody ever manage to escape?

Yes, an incredible escape took place just here. On July 27th 1929 Francesco Fausto Nitti, Carlo Rosselli and Emilio Lussu, three of Italy’s most prominent anti-fascists, managed to avoid the surveillance of the Carabinieri and the Fascist militia and escape on a motorboat that had come to collect them. It was all organised by Paris-based Italian anti-fascists.

Yes, an incredible escape took place just here. On July 27th 1929 Francesco Fausto Nitti, Carlo Rosselli and Emilio Lussu, three of Italy’s most prominent anti-fascists, managed to avoid the surveillance of the Carabinieri and the Fascist militia and escape on a motorboat that had come to collect them. It was all organised by Paris-based Italian anti-fascists.

Credits: Centro Studi Eoliano

In 1919 Benito Mussolini founded the Fascist organisation (known as the Fasci di combattimento) in Milan. Supported by veterans of the Great War and the middle classes, the movement became the National Fascist Party in 1921.

On October 28th 1922, the Fascists marched on Rome. King Victor Emmanuel III did nothing to prevent the initiative, and entrusted Mussolini with the task of forming a new government.

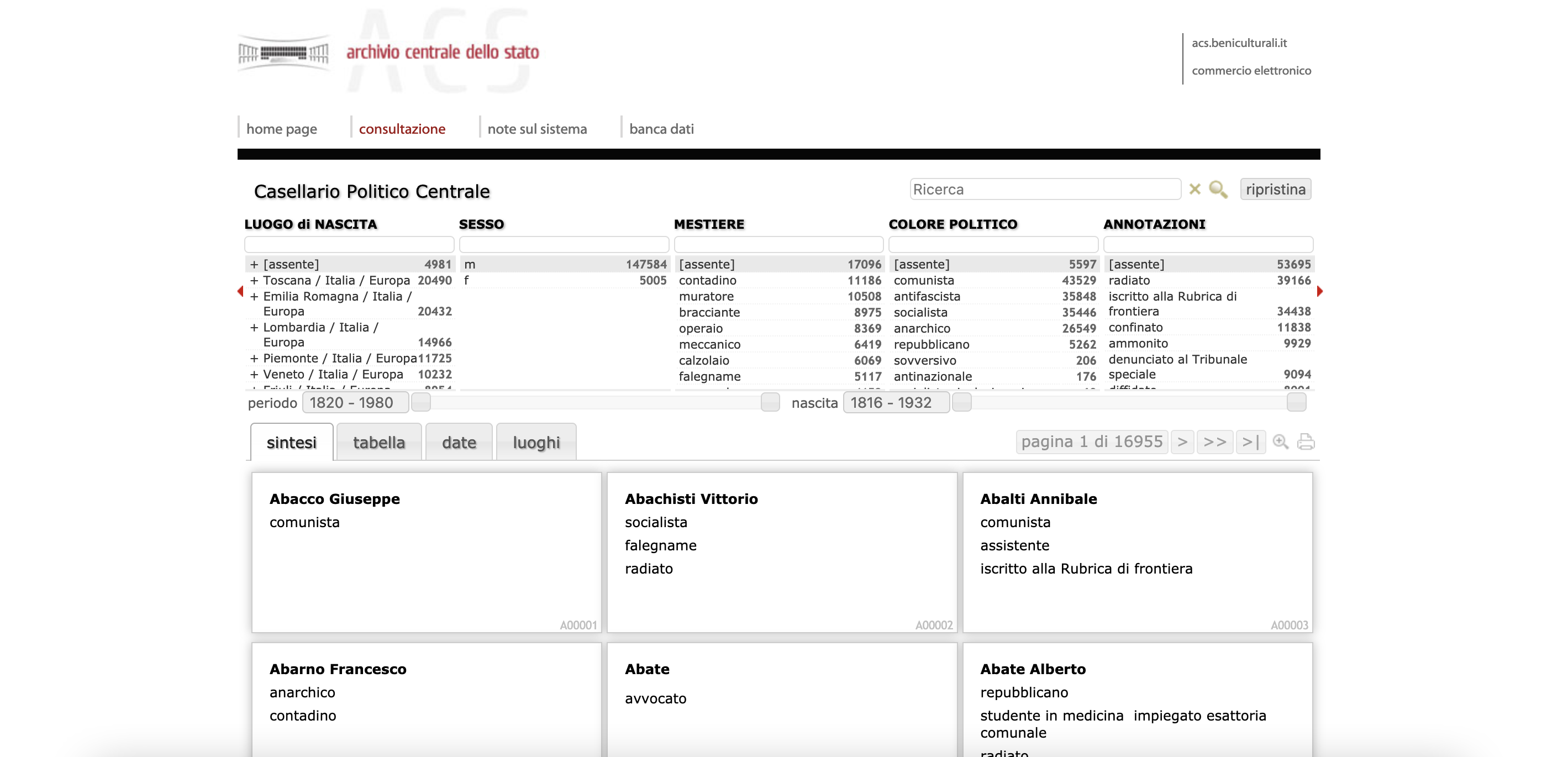

The future Duce thus laid the foundations of his dictatorship: he restricted political and trade union freedoms, set up a special court and secret police, and violently repressed his opponents, who were forced into prison, exile or confinement, if not physically eliminated. Between 1923 and 1926 the priest Don Giovanni Minzoni, the socialist politician Giacomo Matteotti, and the intellectuals Piero Gobetti and Giovanni Amendola lost their lives at the hands of the Fascists. In 1937, the communist leader Antonio Gramsci died after 11 years in prison; the same year, Carlo and Nello Rosselli, the founders of the Justice and Liberty movement, were assassinated in France.

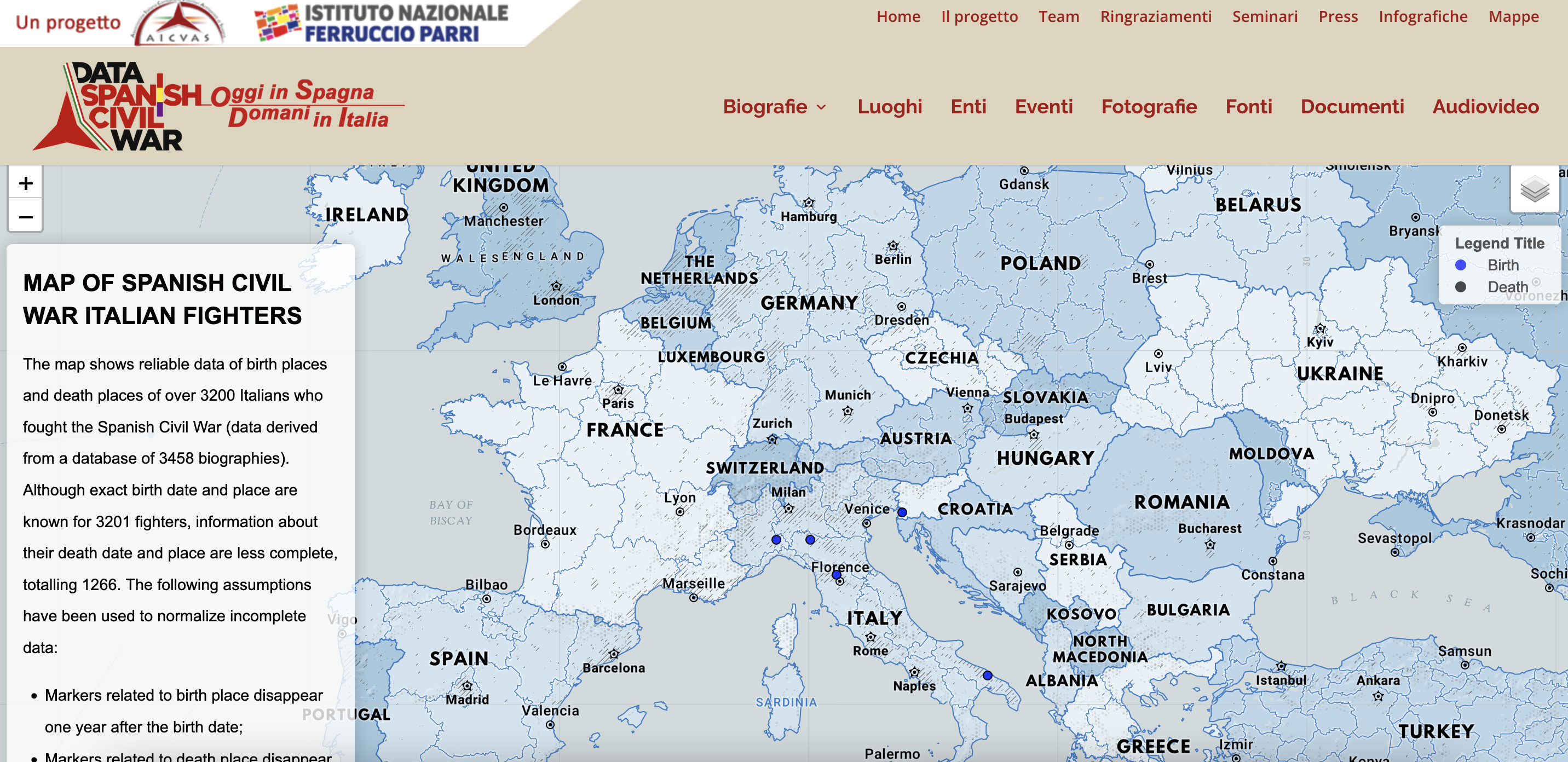

From the beginning of the 1930s, a new generation of anti-fascists took shape, ready to fight against the dictatorships sweeping across Europe. One example of this was the several thousand volunteers of the international brigades, including over 4,000 Italians, who enlisted in defence of the Republic in the Spanish Civil War. In Italy, too, there were growing signs of discontent with the regime, even if its stability was not compromised.

The public debate on the memory of Fascism in Italy has been and still is complex. This difficulty in coming to terms with the past has taken the form of a politically inspired revisionism or, more simply, has led to attempts to soften the image of Italian Fascism, which is then reduced to a ‘good-natured’ regime based on the stereotype of Italians as ‘good people’.

The rise of populist right-wing movements and the erosion of anti-fascism have favoured dangerous simplifications, the calls for a general oblivion of the past, and a growing tolerance towards the use of the symbols and the language of the regime. And every year hundreds of nostalgic people still go on a pilgrimage to Predappio to visit Mussolini’s tomb.

Many traces of Fascist architecture still mark the Italian landscape: monuments, public buildings, entire neighbourhoods. The management of this heritage is still highly debated: preserving, demolishing, repurposing. On the other hand, the places of imprisonment, exile, torture and assassination of opponents, which have been restored, made accessible and transformed into museums and interpretation centres, are now crucial tools to protect the memory and the values of anti-fascism.

Places of interest

(Sarzana, Liguria)

(Milan, Lombardy)

(Bolzano, Trentino-Alto Adige)

(Fratta Polesine, Veneto)

(Predappio, Emilia-Romagna)

(Rome, Lazio)

(Aliano, Basilicata)

(Ghilarza, Sardinia)

(Ventotene, Lazio)

Watching /reading tips

Il conformista

Movie

(Bernardo Bertolucci, 1970)

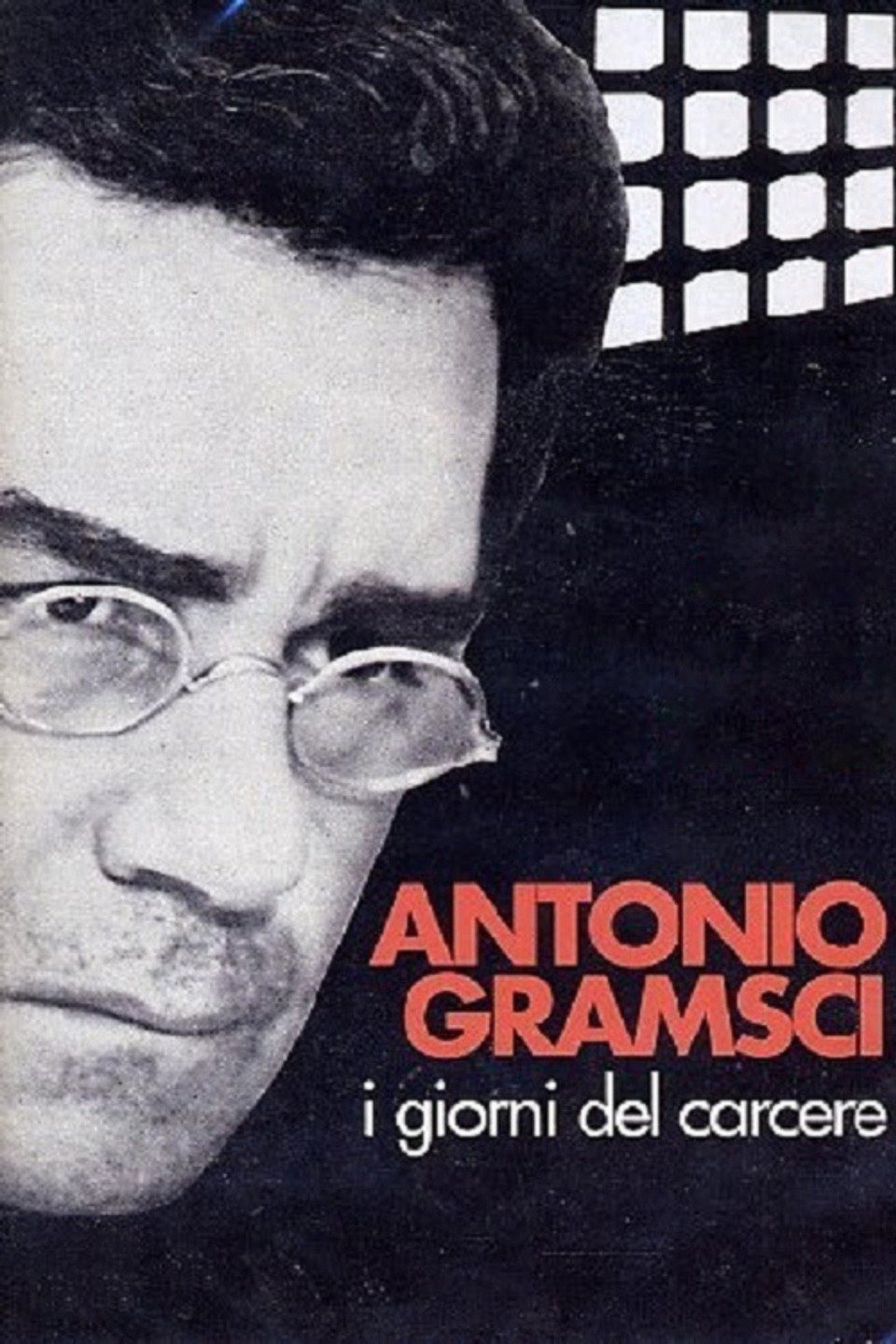

Antonio Gramsci

I giorni del carcere

Movie

(Lino Del Fra, 1977)

Cronache di poveri amanti

Movie

(Carlo Lizzani, 1954)

M

Il figlio del secolo

Book

(Antonio Scurati, Bompiani, 2018)

To know more